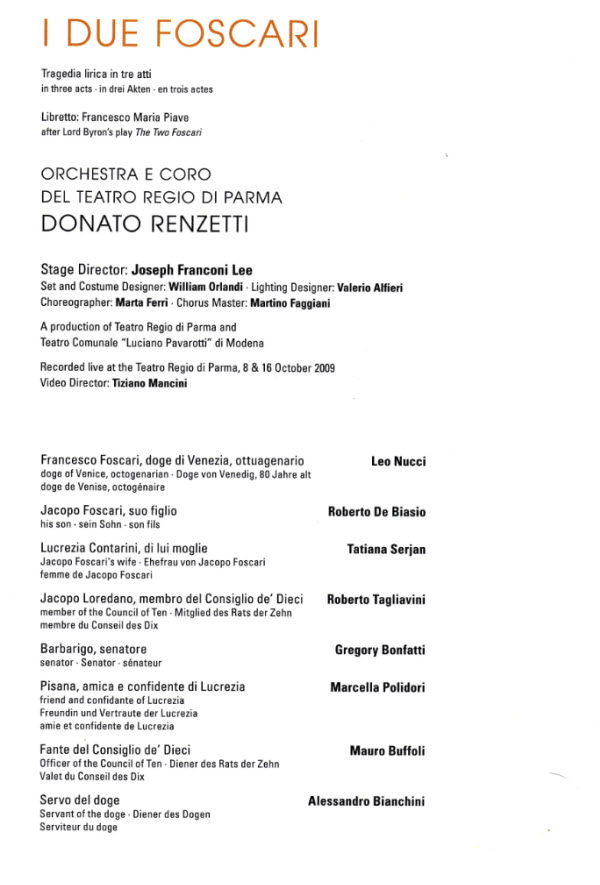

Verdi’s sixth opera was first performed in Rome in November 1844. Its libretto (by Francesco Piave) was based on Byron’s play The Two Foscari. Despite much beautiful music, the work has to be judged a failure. Three years after its premiere, Verdi himself summarized the reasons for the work’s failure. “In subjects which are naturally gloomy if you’re not careful you end up with a deadly bore – as for instance I Due Foscari which has too unvarying a color from beginning to end.”

Verdi’s sixth opera was first performed in Rome in November 1844. Its libretto (by Francesco Piave) was based on Byron’s play The Two Foscari. Despite much beautiful music, the work has to be judged a failure. Three years after its premiere, Verdi himself summarized the reasons for the work’s failure. “In subjects which are naturally gloomy if you’re not careful you end up with a deadly bore – as for instance I Due Foscari which has too unvarying a color from beginning to end.”

Byron’s dreary five act play was shortened by Piave to three acts. Jacopo Foscari, the tenor, is a victim. While he has much to complain about, his constant kvetching becomes progressively annoying as the opera progresses. Much of the music he sings is quite lovely, but a listener can take just so much gloom. To make things worse the villain, Loredano, is a bit player. The opera desperately needs a fully fleshed bad guy.

Jacopo’s father, Francesco, is 84 years old and is the doge of Venice. He’s a figurehead however, controlled by the Council of Ten and unable to help his son who after three acts of mistreatment gives up and dies off stage. Piave’s compression of the original play makes much of the action in the opera unintelligible. There are hints here and there as to why Jacobo is in jail and why the villain, Loredano, hates the Foscari family – but you have to pay close attention to the libretto to really understand why. The only person who seems to do anything, and she doesn’t do a whole lot, is Jacopo’s wife Lucrezia who also is a big complainer.

Despite a poor story choice, Verdi has written some very beautiful music that in part makes up for all the gloom. Notable are Jacopo’s arioso in scene 1 of Act 1, the chorus of consolation in scene 2 of the same act, the duet between Lucrezia and the Doge in scene 4 of the first act, the love duet (if such is possible in this opera) in scene 1 of Act 2, and the great baritone aria (see below) in which the Doge indignantly react to the Council’s decision to force his abdication.

The most forceful role in the opera is Lucrezia. Her vocal requirements are similar to those of Abagaille in Nabucco. Soprano Tatania Serjan is very attractive, but the part is far beyond her vocal resources. In the first two acts her sound was produced entirely from her throat and her voice seemed ready to shred at its next note. She sounded a little better in the final act which makes me wonder if that act was recorded on a different day from the first two.

Tenor Roberto De Biasio only started singing professionally in 2006 after a career as a flutist. He has sung six performances at the Met where he received very good notices. He has a steely tenor which seems right for Verdi’s spinto parts.

The meatiest (though not the biggest) part, is that of the Doge – Francesco Foscari. Veteran Leo Nucci (he was 67 at the time of this staging) swallowed the part whole. Though he looked every bit the 84 year old he was playing, his voice was four decades younger. Here’s the aria Questa dunque e l’iniqua mercede which was so vociferously received that Nucci broke character to acknowledge the cheers and applause. Actually, it didn’t take much to get him stop being the Doge and resume being the Italian baritone. Nevertheless, his ability to sing Verdi’s demanding baritone roles at such an advanced age makes him a geriatric wonder.

Conductor Donato Renzetti’s leadership was brisk and forceful. He did as much as was possible to lessen the lachrymose character of the opera. The staging by the Teatro Regio was typical of the Verdi series so far. Spare, but effective, sets accompanied by sumptuous costumes with vivid primary colors. The video direction, as has been the rule in these productions, was very good. The Met’s HD TV team could learn a lot from watching these videos.

In summary, this video makes a good case for I Due Foscari. A stronger soprano would have made the case better. Still, it’s Verdi becoming Verdi and thus intrinsically of great interest.

[…] like a trumpet and then like a cello. Tenor Roberto De Biasio did not sound as steely as he did in I Due Foscari which was recorded the previous […]