The New England Journal of Medicine just published a paper examining whether the cholesterol lowering drug rosuvastatin (brand name Crestor) prevented venous thromboembolic disease. The study concludes that statin therapy does reduce the likelihood of this disorder. But like so much in medicine there’s less here than meets first glance. To begin with all the patients studied had CRPs (C-reactive protein) of 2 mg/L or more. CRP is a nonspecific marker of inflammation. The higher it is, all other things being equal which they never are, the greater the likelihood of developing heart disease. A value of 2 or more is elevated compared to a completely healthy person. In health, the protein is usually so low that it’s virtually undetectable. Subjects with LDL cholesterols greater than 130 mg/dl were also excluded. 17,802 “healthy” men and women were followed for a median duration of 1.9 years. Half received 20 mg/day of the statin while the remaining half were given a placebo.

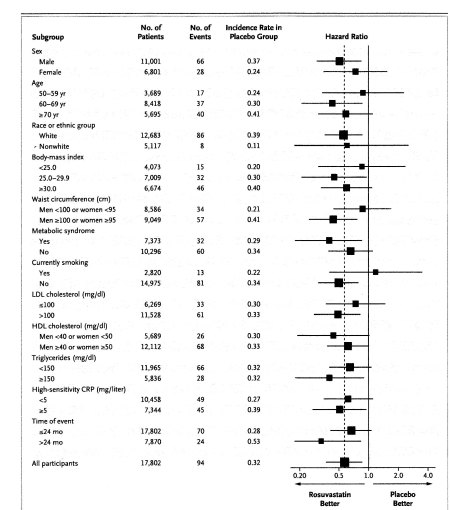

This study is a good example of what happens when you combine statistically significant data with those that are not and come up with an overall statistically significant result. Most people stop at the conclusion; the press certainly does. But if you subject the data to analysis they break down to something close to incoherence. The essential data from the study are presented below.

If any of the error bars straddle one the results for that group are not statistically significant. Thus the data show no effect (effect here is meant to be synonymous with a statistically significant effect) of statin treatment compared to a placebo in women. No effect in subjects less than 60 or more than 70 years of age. No benefit for nonwhites. No effect in subjects with BMIs less than 25 or more than 30. No effect on smokers. No effect in subjects with LDLs less than 100. No effect in subjects with CRPs less than 5 mg/L. Yet when you look at all participants the protective effect of statin treatment is highly significant.

Is this study likely to change the way physicians prescribe statins? Not if they read the study carefully. Would I add statin treatment to the regimen of someone who lacked risk factors for cardiovascular disease? No. Would I give it to someone who was at increased risk for venous thrombosis, but who had no other indication for statin treatment? Again no, especially as the study showed no reduction in the rate of the main serious consequence of venous thrombosis – pulmonary emboli. This paper falls under the category of interesting but useless – at least for now.